27-Jun-2025

D-Day Veteran Ken Cooke Becomes Memorial Ambassador

On Monday 23 June, the Trust was delighted to appoint D-Day Veteran Ken Cooke as Memorial Ambassador.

Ken joins fellow Ambassadors Ken Hay MBE, Stan Ford and Mervyn Kersh.

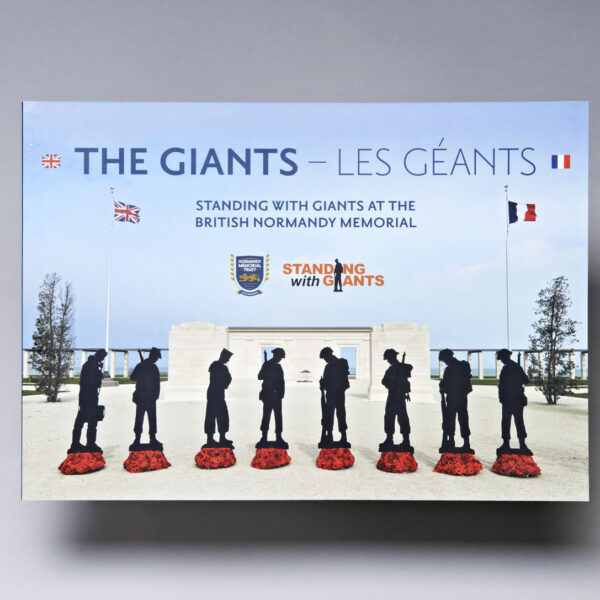

Ken at the Standing with Giants installation for D-Day 80. Credit – Paul Reed

On his appointment, Ken said –

“I was a member of the 7th Battalion, the Green Howards, and I landed on Gold Beach on D-Day, 6th June 1944. I’m very proud to have been asked to be an Ambassador for the British Normandy Memorial. It means a great deal to me — to help remember the lads who didn’t make it home, I’ll do the role to the very best of my ability.”

On his appointment, Lord Richard Dannatt, chairman of the Trust said –

“I am truly delighted that D-Day Veteran Ken Cooke has accepted the role of Memorial Ambassador. Ken served with the Green Howards, where I also began my military career — a regiment that played a significant and courageous role on D-Day and throughout the Normandy campaign.

Ken landed on Gold Beach, just below where the British Normandy Memorial now stands, and his passion for sharing the lessons of the past, especially with young people, will be a great asset to the Trust and to our Winston Churchill Centre for Education. We’re honoured to have him help us carry this legacy forward.”

Ken’s D-Day Story – in his own words

I was 18 when I got called up. I went to Richmond Barracks in Yorkshire for my basic training — six weeks learning about weapons, marching, map reading, all that. After we passed out, we did a set of tests — puzzles and bits of equipment we had to figure out. I was given a pile of metal parts and had no idea what they were. Turned out to be a bicycle pump. I’d never had a bike, so I didn’t recognise it at all!

After that, we were assigned to different regiments. Some lads went into tanks or signals, but most of us, including me, went into the infantry. I joined the 7th Battalion, the Green Howards.

We moved around different camps doing more training — assault courses and exercises — and eventually we ended up near Southampton at an American camp.

We dumped our gear in some tents and went further down the field, where an officer was waiting behind trestle tables covered in photos of the French coast.

They told us those were from people’s holiday snaps. The government had asked people to send in their holiday photos from France to help plan the landings. Then they gave us what they called invasion money — not worth anything really — just something to use once we landed.

We were assigned to American Liberty ships. The Americans welded their ships; ours were riveted. Ours was called the Rapier. We settled into our bunks, played cards, read, tried to sleep.

One day a Dakota flew over, and the officer said, “See that? The black and white stripes on the wings — those mean it’s one of ours. If you see any without, that’s the enemy.”

There were that many ships in the harbour that someone said you could’ve walked across without getting your feet wet.

On the night of June 5th, we felt the ship moving. At about half past three in the morning, reveille went. Breakfast was scotch porridge with salt — horrible — a corned beef sandwich, a mug of tea, and a tot of rum. That rum was for courage, I reckon.

By four o’clock, we were on the top deck. We looked out and saw the explosions and smoke on the shore. The officer said, “Right lads, down into the landing craft.” We went down scrambling nets — the same ones we’d trained on at Aldershot. Now we knew why.

The big ship was going up and down, and so was the landing craft. You had to time it just right. Some lads got it wrong and nearly went through the net or fell, but we got everyone down safely on ours.

Later, we heard stories of others who weren’t so lucky — fell in and drowned with all their kit or got crushed between the ship and the landing craft.

Our driver got us to within three feet of dry land. I stepped off into about six inches of water. People ask me what it was like landing on the beach. I always say: it was like stepping in a puddle and thinking, “Oh no, my socks are wet.” That’s what I was worried about — my socks. Not the shells, not the bullets — just my socks. Strange, but that’s how it was. All adrenaline.

When I look back now and see photos of lads up to their necks in water, holding rifles over their heads — I think, here’s me moaning about my socks.

The beach was chaos — smoke, fire, explosions. The engineers had gone in before us to clear the mines, but they missed a few. Some landing craft hit them and went up. We were lucky.

We got off the beach. But it was the next day that it hit home. At breakfast, we looked around and said, “Where’s George? Where’s Billy?” And someone said, “They went down on the beach and didn’t get back up.”

That’s when you realised — this was real. You either got through or you didn’t.

I’ve always said, I’ve been very, very lucky. I got through. Others didn’t. I’ve had 80 more years of life than some of the lads who were with me that day.

Ken at the ‘York Normandy Veterans’ bench at the Memorial. Credit – Paul Reed

Ken’s message to children and young people

I always tell young people that it’s really important to learn history — especially the history of the last 80 years. You need to understand why we went to Normandy, what happened there, and what it meant.

When I speak to schools, I say to the students: “Now it’s up to you. It’s up to you to make sure that what happened to us — what we went through — doesn’t happen again.”

We often finish our talks by asking them to put their hands up and promise us veterans that they’ll do that. That they’ll remember. And that they’ll carry it forward.

Ken at the Memorial. Credit – Paul Reed

On 8 August 2025, Ken turned 100. This is what he had to say about reaching the milestone: