Dennis Woodcock

This story is shared by the Trust with kind permission from Tim Woodcock, Dennis’ son

Like many veterans, Dennis Woodcock did not really talk about his wartime experience. Having been brought up in an active Quaker family, where pacifism was the norm, he did not want to serve in a combat role. But he was fully prepared to accompany soldiers into battle in order to care for those who were wounded.

He took the opportunity to serve with the Friends Ambulance Unit (FAU). But after his eightieth birthday, certain records, citations and documents were rediscovered by his family. The response to these various papers was, “That’s all splendid, Grandpa, but what did you actually do? So he began to write down his story. As he says: “It is not very easy to write a readable story when the truth is that an awful lot of war-time activity, or non-activity, is sitting about being bored. I have tried to pick out those events that do, I hope, make an entertaining tale.” The following extracts are taken from his story published on denniswoodcock.net

“I was the second son of Quaker parents and I and my elder and younger brothers all went to the Quaker boarding school in Yorkshire called “Ackworth”. I went at the age of eight years and stayed there until I was eighteen. Unlike my two brothers I was extremely happy there largely due to the fact that I was good at cricket and football. It was the sort of school where the Captaincy of the Soccer 1st X1 carried infinitely more prestige than the position of head boy or head prefect. Although I left school with ample qualification for University I was offered a job with Midland Bank in which my father was a branch manager. It was a boring and meagrely paid position but it enabled me to continue to play football and cricket.

By 1939 it was clear to most people that we should be very lucky to avoid a war with Germany. I had noticed the occasional absence of some of my friends when they attended training camps of one sort or another. I was really only concerned about the next football season, when totally unexpectedly, a letter arrived from the Friends Ambulance Unit asking if I would be interested in joining the first training camp to be opened in Birmingham in September. This letter went to all young men of the right age who had been in Quaker schools.

I replied and after an interview I was accepted. The Friends Ambulance Unit had been created in World War One and had earned an enviable reputation. It had been disbanded when that war ended but was now reconstituted. My invitation and acceptance as a member of the first camp could hardly have been better timed. I informed the manager of the Midland Bank branch where I worked and he accepted that I had, in effect, been called up. The bank gave a party to see me off as the first member of the staff to “go to war”.

The days at the first camp passed very quickly. We did all get reasonably fit, and most learnt to drive after a fashion. We could apply bandages and splints and tie the right sort of knots. One or two of us even became quite good cooks. About the middle of November the whole camp was moved to London where hospital training was organised.”

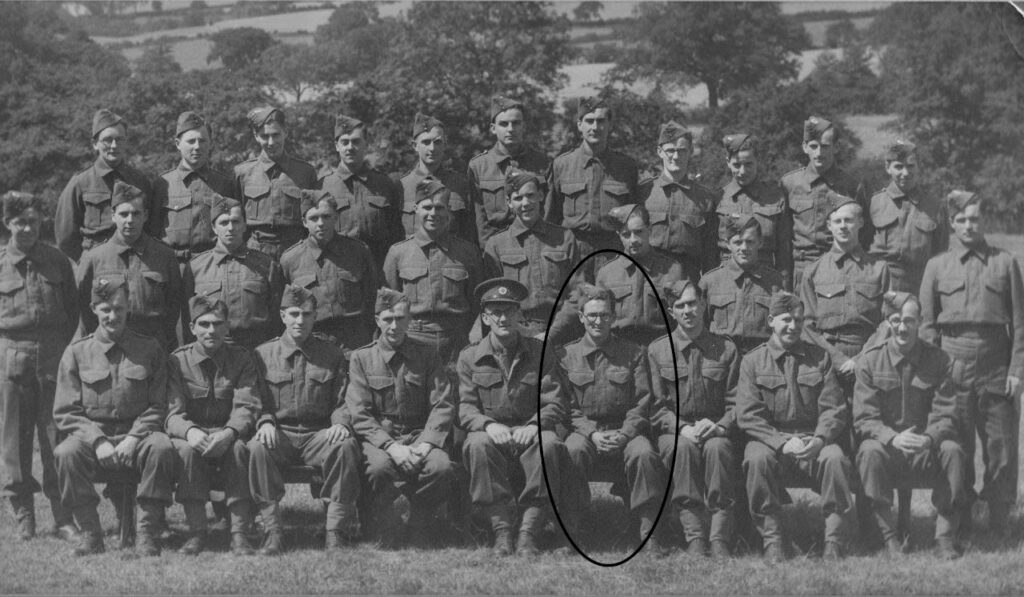

Photo believed to have been taken at the Friends Ambulance Unit Training Camp, Birmingham. Dennis, circled, stands in the second row

Dennis was first deployed to Finland in 1940 after war broke out between Russia and Finland. The Russians wanted a presence on the sea coast and had expected to drive through Finland with ease. But the Finns had put up a fierce resistance. However, they soon had to negotiate an uneasy peace as their lack of fuel oil meant they would eventually lose. He helped to evacuate those living in the territories ceded to Russia and was eventually evacuated back to the UK.

In 1943 he was selected to join the 2nd French Armoured Division in North Africa as the French were desperately short of manpower. He served with the medical battalion of the 2nd Armoured Division run by Sergeant-Chef Larreur. Dennis became good friends with Chef Larreur and corresponded with him after the war until his death some years later. Dennis’ unit provided medical support for the Division during its time in North Africa, and returned with them to the UK in 1944 in preparation for D-Day. The FAU unit was one of three companies which formed the 13th Medical Battalion of the 2nd French Armoured Division.

3rd Company, 13th Medical Battalion. Dennis Woodcock, circled, sits in the front row (Source: https://www.marinettes-et-rochambelles.com/)

Men of the 3rd Company, 13th Medical Battalion. Dennis Woodcock sits, second row, left (Source: https://www.marinettes-et-rochambelles.com/)

“We joined the widespread preparations for The Great Invasion. The Division was spread around the countryside in the vicinity of the City of Hull and we had been there for several tedious weeks after arriving from North Africa. My boredom was relieved, for a few marvellous hours by the unexpected arrival of my wife, Jan, looking very fetching in her W.R.N.S. uniform. All leave had been cancelled at the decoding centre at Bletchley Park where she was stationed. However, having good friends to cover for her and disguised as a civilian she somehow managed to turn up at the other end of the country to brighten all our lives for a few hours, before returning to base, her absence undetected.

It was not long after Jan’s visit that we were told to be ready at 5 a.m. the next morning, with all our gear aboard and engines running. The whole Division moved off promptly and, apart from ten minute stops every hour we kept moving until, in the dark, we drove into a large wire-caged enclosure somewhere near Dorchester.

We were fed and had a few hours sleep before moving off again for the quays near Southampton. There, our liberty-ship, the “Oliver Wolcott” was one of many similar vessels stretching as far as the eye could see.

An American Petty-Officer told me to leave the key in the ignition and go aboard. As I walked up the gang-plank my home for the last six months swung dizzily past my nose and sank out of sight into the hold. At least we were on the same ship!

On board, the American way of life was very apparent. I followed my nose to where the delectable smell of good coffee led me. In a spacious dining-canteen I was offered an enormous meal of rather unfamiliar content. Beyond was a comfortable area to lie down if one wanted to. I decided to relax for a minute or two before exploring the ship; and woke up about six hours later!

We were obviously at sea and I made my way on deck. Dawn was breaking and the coast was just visible to the left, or perhaps I should say ‘to port’. The immediate impact of the rest of the view was of a seascape full of ships. It took a second or two to realise that, apart from the quantity of ships, the odd thing was that they were all going the same way. We were going very slowly and it was some hours before we met a similar mass of shipping coming from the north. Each great convoy turned east and we sailed slowly towards the French Coast.

When I awoke next morning we were anchored in the lee of an enormous structure which I later realised was the “Mulberry Harbour”. We were close enough to be deafened by the noise of hammering, riveting, diesels and shouting. From the shore there was a constant rumbling of gun-fire but the early morning mist prevented us seeing anything clearly. Our extremely hearty breakfast was interrupted by the sound of the anchor being raised and we moved, alone this time, slowly westward along the French coast of Normandy.

We had evidently been anchored off the most easterly of the four invasion beaches. We could just see through the mist the activity at the next two as we sailed past. We then moved much nearer to the coast and anchored off the most westward landing area known as “Utah”. Offshore, just visible in the mist, were two American battleships which fired their huge guns every-so-often leaving our ears ringing. We were now near enough to the beach to see great activity. Tiny figures and vehicles were moving everywhere, making the beach look like a disturbed ant-hill. Apart from the battleships the only war-like signs were an occasional puff of smoke rising inland and, from time to time, aircraft flying over. They usually came and went so fast it was not possible to distinguish their nationality but the gunners seemed to assume they were German and fired everything available into the air.

As soon as the anchor had splashed into the sea a large area of what I had assumed to be seaweed began to move towards us. It was our “Rhino” coming to collect us. It was moving very slowly and some time elapsed before I could distinguish the two tiny engine sheds at the stern. A friendly sailor on the “Oliver Wolcott” told me there was plenty of time to go down to the mess room and collect anything eatable; “Stuff your pockets, you won’t get anything on that thing!”

At last the strange vessel was secured alongside and the public address system told all passengers to assemble on the port side. We were instructed that, when ones own vehicle appeared out of the hold, one had to scramble down the boarding net hanging over the side and report to the “C.B.” [CB’s were the odd-job men of a division of the American Army’s “Construction Battalion” of “CB’s”, as they were known] who would be waiting. To my consternation my ambulance appeared first. I had hoped to learn from the efforts of some of the others, but it was not to be.

In fact, once over the ship’s rail it was not very difficult but both hands were needed, hence the instruction that nothing was to be carried. The “C.B.” waiting for me was a laconic, friendly man clearly relieved to find that I was English. He said I was to drive, bumping and rolling over the deck to where the other crew member was standing with two bats in his hands, similar to those used by aircraft handlers. I was to drive to the bow within inches of the edge of the first pontoon. Finally, when correctly placed it was explained that if the first vehicle was right, all the others would follow easily whatever language the driver spoke (hence their relief to find I spoke English).

Once we were away from the protection of the ship the wind and waves became many times fiercer. Those who were sick became sicker and the whole effect was of an endless earthquake. The vehicles were not tied down in any way and all of us, except the “C.B.s”, were terrified. Most of us would have preferred to face the Germans any day.

However, after a while it dawned on us that we were not going to sink, at least not yet. Then disaster struck. A wave, bigger than the others, sloshed over the pontoons and one of the engines made a despairing series of misfires and died on us. The “C.B.s” took this in their stride, one going to the expired engine with a bag of tools, the other to pore over the survivor to coax more power out of it. An hour later and it was clear that we were not going to make that part of the beach where the landing party were waiting. In fact it seemed doubtful if we should make the beach at all. There was an appreciable westward current carrying us away and again we felt fear for our survival.

Once again the stoical lack of concern by the “C.B.s” brought relief to all. Their first move was to brew coffee in the shed of the engine still roaring away. After being given a cup I was asked to go round selecting, as the “C.B.s” said, “a reasonably intelligent fellow” in each area, preferably one not too sick. I was to release him from confinement in his cab and instruct him to tell all the others that everything was under control, but we would be a bit late.

Privately, I asked if everything was under control. “Oh, sure”, was the reply “providing this good lady goes on performing.” That was said with a hearty slap on the petrol tank of the still functioning engine. It seemed that the tide was due to turn soon and there was a possible beaching area which we could just about make.

Meanwhile the beach party had been moving along, keeping pace with us, and eventually the “Rhino” ground to a halt on a strip of beach just wide enough, with nasty looking rocks each side.

Now came the disembarkation and obviously I had to go first. The Senior “C.B.” told me that the trick was to keep my eyes firmly on his bats in the driving mirror. He would keep me on the ramp and would give me a signal when I was to transfer my gaze to the bats of the beach-master. The one thing I was not to do was to look at the water. When on the sand the beach-master would be replaced by a jeep with distinctive black and yellow stripes on its rear. I was then to follow that jeep and not stop until instructed. It all sounded so unlikely to work but the calm and clear instructions gave confidence, and work it did.

My only regret is that I had no opportunity to say thanks to the “C.B.s”, the beach-master and the jeep driver who finally, hours later, delivered me and a large part of the division, following behind, into the rapturous welcome of Sergeant Chef Larreur. He executed a magnificent stage bow and said, “Monsieur Woodcock, welcome to my native land.” The French do have an ability to make a simple event into a great occasion.”

Ambulance driven by Dennis Woodcock. Each ambulance was given a name and Dennis named his after his wife, Janet Elizabeth (Source: https://www.marinettes-et-rochambelles.com/)

Sometime later, after crossing the Normandy beaches, we became part of General Patton’s Army group that broke out of the beach-head and set off South East, too far South to take Paris. After being the spearhead division of that army for about a week we were told to pull off the road to let an American division roar past us. It was the first time I had seen a whole armoured division go past in one convoy. It seemed endless but finally we set off again, this time to the North. Immediately the whole division was seething with rumour. Were we really going to Paris? The possibility became more and more likely and finally we were halted on the main road from the West to the capital. The road was blocked by a German strong point about five miles ahead where an American infantry division had so far failed to break through.

Although no official announcement had been made it was pretty certain that we would at least be part of the force to relieve the embattled people of Paris. The Resistance had risen up about a week before and the Germans were bottled up in five or six enclaves. However, German reinforcements had got through and the Resistance were running short of ammunition and everything else. Unless help arrived during the next few days the Germans would regain control.

It is difficult to describe the excitement that was generated among the Frenchmen at the prospect of liberating their Capital. Many of our men actually came from the city but many more had relatives or friends there. Paris represents something quite different to French people than London does to the English. Londoners would like to believe that their city represents the high point of the culture of the nation, but few who live outside London would agree. For the French, at least in 1944, Paris was France.

Rumour and hearsay were everywhere but the story of Leclerc’s appeal to the American, General Bradley, commanding the army group is probably somewhere near the truth. He is said to have asked if we could take over and promised to have the road open before nightfall. Bradley agreed and Leclerc used the method of a tank charge which had been practised in Morocco. The German strong point was ideally suited for this form of attack.

The enemy were strongly ensconced in a two-storey garage and showroom building on the East side of a cross-roads. They had four, eighty-eight millimetre, anti-tank guns in the building and several others hidden away in the surrounding fields in order to forestall any attempt to by-pass the strong point. Leclerc assembled six Shermans just out of sight of the Germans beyond a slight rise in the road, with six more tanks behind. The road was just wide enough to take six tanks abreast.

The Germans were taken completely by surprise when the tanks came roaring over the crest of the rise, going flat out and all guns firing. The enemy were evidently as near the end of their endurance as the Americans had been. They turned and ran.

I did not see this epic charge but later I drove past the scene and the debris of the battle clearly confirmed what we had first thought to be rather exaggerated reports.

After that engagement the road to Paris was open. We received orders to get going immediately and rendezvous at Rambouillet. I arrived there during the night and found a very well organised collecting area. Black-out restrictions were ignored and the Resistance people had everything ready for us.

Somebody had grasped very clearly what the ambulances would require. There would be three categories of casualty; army, civilian and German. Army cases would go to our own Field Hospital, even then being set up on the outskirts of the city. Civilians would go to the city’s hospitals and the German Air Force Hospital in the city would be left to cope with German cases. The key to the efficient working of these arrangements would be a guide in each ambulance who knew the city well, knew which hospital had beds available and could speak the language of the driver. Whoever had organised this had done brilliantly. My guide, Madelaine, was a twenty-two year old second-year medical student who knew every back street and short-cut, was efficient and, as a bonus, was a very attractive girl.

There has been a lot of speculation since the great day when we took the city as to who was the first British man to get there. It is all quite pointless because we were divided into our usual small units; in my case a force of six Shermans, one ambulance with others on call and two half-tracks of infantry. Our objective was the Avenue Victor Hugo and the Place de L’Etoile.

Several strong points were dealt with on the way to our rendezvous but the overriding problem was the size of the crowds of civilians. They just swarmed all over us. They kissed us, fed us, pressed drink on us and offered even more exotic and impractical entertainment if only we would stop. However, we were soon reminded that there was a war going on. Moving slowly through the crowds we were suddenly sprayed by the indiscriminate firing of machine guns from the roof tops. We had been warned of this possibility and the tanks and half-tracks were ready with instant response. The vast crowds of civilians showed their familiarity with gun-fire by disappearing as fast as they had appeared, but leaving several sad heaps lying in the road. Madeleine showed her mettle on that first attack. She had done a stint in casualty at her training hospital and was quite as fast and efficient as I was, probably more so. We had the first of the civilian wounded into a nearby hospital within minutes of the shooting.

The day went on like that with greater or lesser delays and it was growing dark when we finally drove into Place de L’Etoile. We were directed to a piece of pavement reserved for us which was to be our base for the next few days.

Madeleine announced that she was going home and produced a bicycle in some mysterious way. I noticed a large bag suspended from the handlebars but was too tired to worry. Later, after a short sleep, I was clearing up and noticed that my dirty clothes and my slightly better uniform were missing. The bag on the handlebars was explained.

The scene in the Place L’Etoile is one that I shall always remember. Four tanks were arranged together in the middle of the Square with planks laid across their turrets. Lights had been erected and leading entertainers of the day produced a continuous cabaret. The only names I can remember are Maurice Chevalier, Edith Piaf and Yves Montand but there was a constant stream of very glamorous women belting out their particular sort of songs to the cheers of the assembled soldiers. All I wanted to do was sleep which I did succeed in managing in short spells. We were continuously on call, so my sleep was fitful to say the least.

Madeleine reappeared, literally at day-break, with my best uniform cleaned and pressed and hung on a clothes hanger! All my clothes were washed and mended and, to cap it all, a box of delicious cakes were included. The family must have been up all night; and Madeleine had already got the list of available beds and a map of the streets still under German control.

After breakfast our section was detailed to capture a large warehouse area bristling with eighty-eight millimetre guns. The Resistance people begged to be allowed to go in after the initial bombardment but were refused. Their actions in such circumstances, when the enemy were clearly defeated, were too barbaric even for our Frenchmen. In fact, after our tanks had surprised the gunners manning the eighty-eights, they all surrendered. That gave us plenty of work because the inside of the building was a nasty sight. We spent the morning sorting out the casualties in order of severity and ferrying them to the German hospital.

This was the pattern until the Germans finally surrendered altogether, leaving the streets to even wilder celebrations which only slowly died down. At length our work became negligible and we were taken sightseeing, although there were few sights to see. The Louvre and the Eiffel Tower were closed, not surprisingly, and one day about a week after the surrender Madeleine and I were sitting on a wall outside her house, with one of my colleagues and his guide, when we clearly heard a heavy gun fire in the distance. Then a shell whined overhead to explode in the city. It was the start of a counter-attack and, within a few hours, we were on the way to deal with it. In fact, it turned out to be little more than a gesture by the retreating Germans but the party was over and it marked the end of an unforgettable period in my life.”

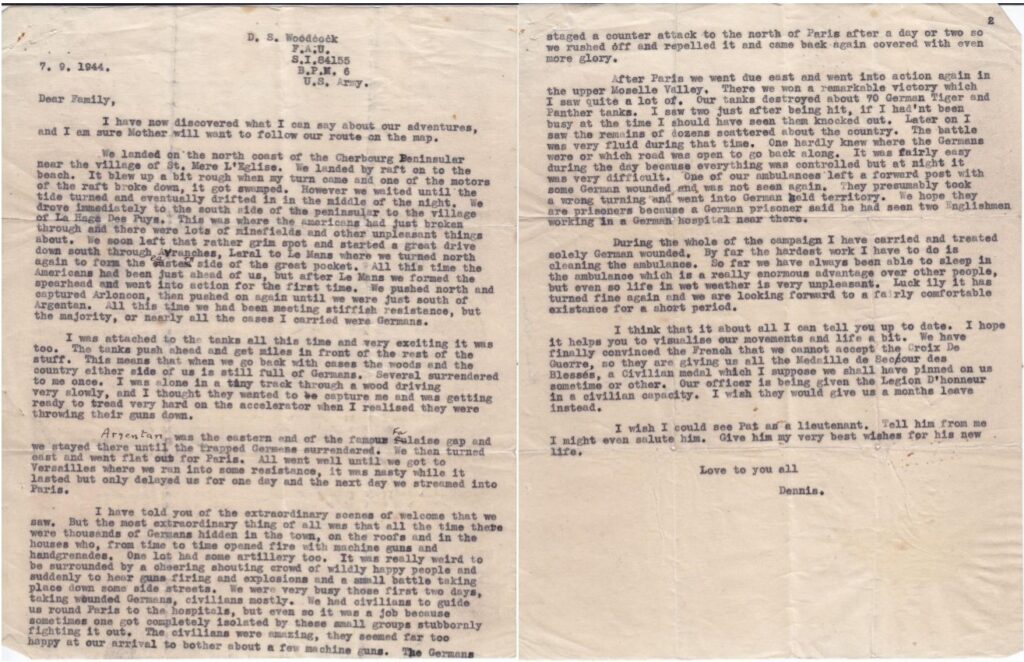

Dennis wrote home in September, describing what he had been doing.

After Paris his unit continued to provide medical support as it advanced through France and Belgium. But Dennis’ part in the war would come to an end in January 1945, when he was seriously injured in the leg when a tank exploded close to him when he went to provide aid to the crew after it had been hit. He was evacuated back to the UK where he spent many months in hospital.

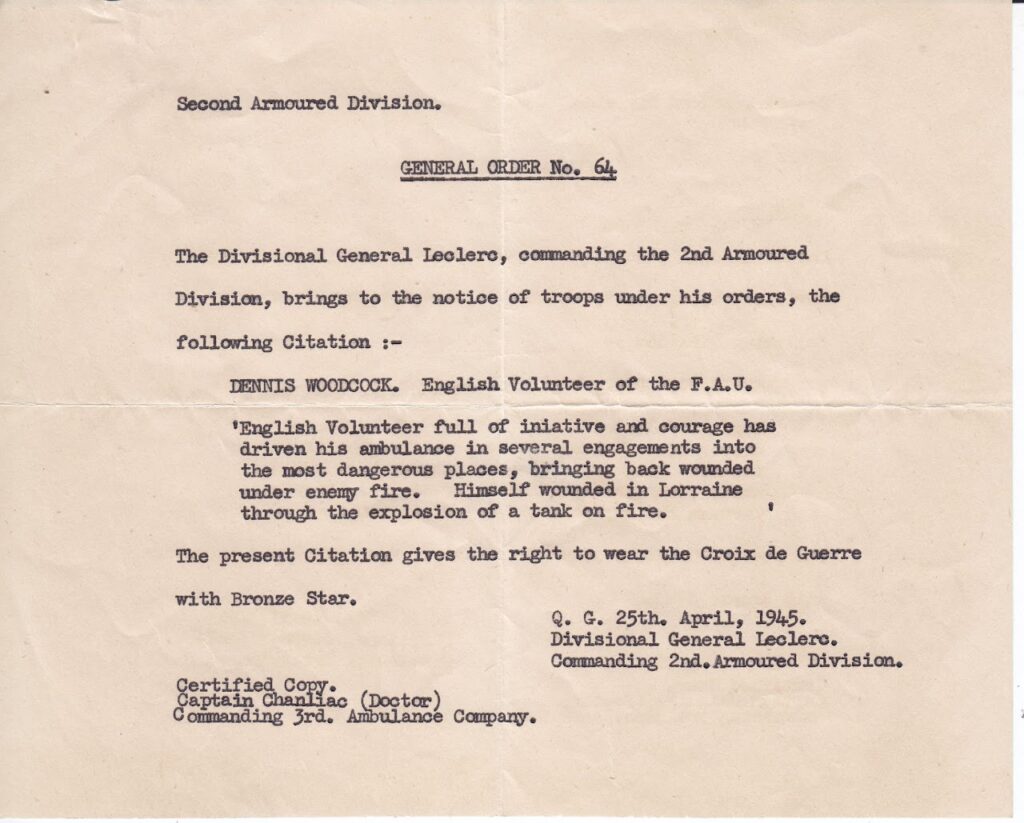

Dennis was awarded a medal of service from the Finnish government and the Croix de Guerre with bronze star in April 1945.

Translation of the Croix de Guerre citation

Dennis’ family do not know precisely how the Croix de Guerre award came about, but Tim put forward the following as a possible explanation: ‘In his letter home, he mentions his group’s reluctance to accept medals. But in 1966 he was interviewed by an author writing a book about Leclerc, (OUT OF THE SAND, Henry Maule, 1966), a copy of which I have. In it Dad has described to the author how he walked into a minefield to rescue the Group Commander, Colonel Langlade, who had been badly injured when he stepped on a mine. I suspect the senior French officer was so thankful for his rescue that he instigated the award of a medal. Only when Dad was severely injured himself and evacuated back to the UK did the medal award get pushed through, when he was not around to object. That may explain the more general wording on the citation referring to his brave frontline work leading to his injury and not the previous minefield rescue.

When the FAU was demobilised General Leclerc sent a letter of thanks for their service “Attached to the 3rd Medical Company, where they constituted the group of ambulance drivers and nurses, despite their thankless and obscure work, they lived up to their pacifist ideal at the very heart of the vast war machine. On all roads or terrains, in all weathers, day and night and very often at advanced posts under enemy fire that would have disturbed a soldier, they displayed the greatest qualities of altruism and charity in order to be at the service of their friends.”

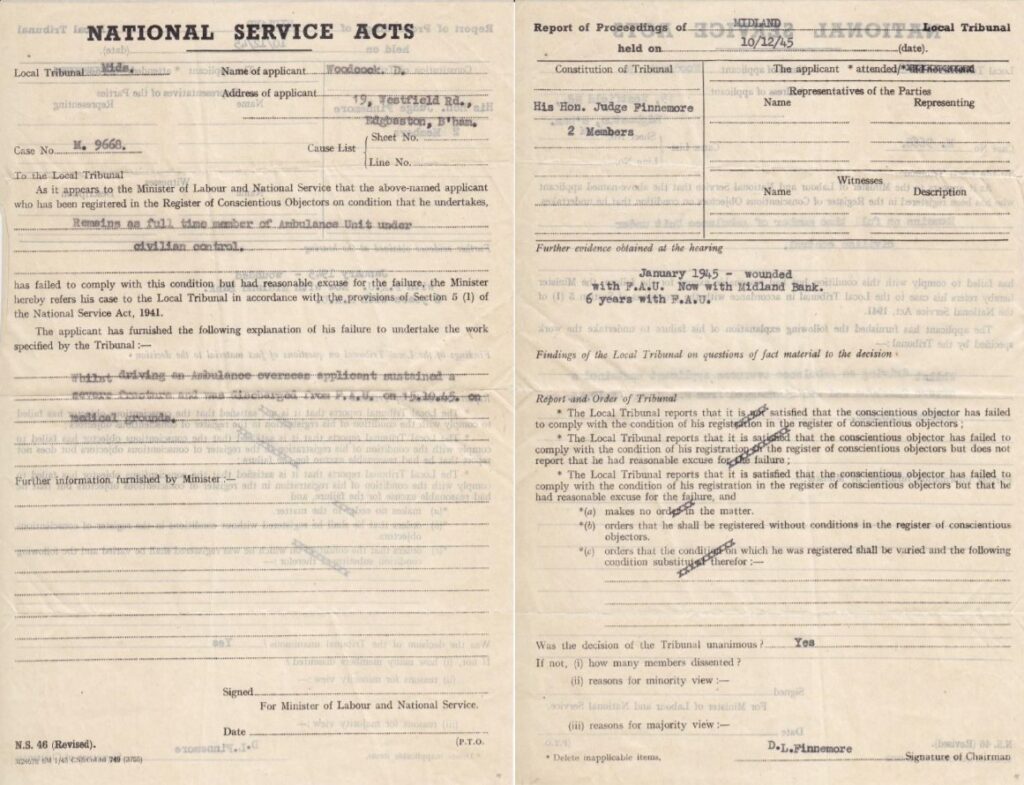

Dennis’ war wasn’t quite over yet. Amongst the documents his family went through was one for a tribunal he was called to attend in December 1945, months after the end of the war. He was clearly registered in the Register of Conscientious Objectors on the condition that he served full time with the FAU.

Tim suggested a possible explanation for the tribunal was that when he was evacuated out of France, no paperwork was completed to cover his absence from the Unit, and so at the end of the war, he was listed as an abscondor. Although the civil service was slow, it was thorough and followed up every case. ‘Sadly we did not pay any attention to this document and so never asked Dad about it. But with the help of of the Library and Archives Assistants at the Quakers in Britain Library we uncovered the story behind it.’

She found a piece in the Quaker weekly journal The Friend (August 3, 1945, p.518). The piece stated that:

Until very recently some Tribunals have allowed conditionally registered C.O.s to write to them informally asking for their conditions of registration to be added to or varied and, if the Tribunal thought fit, this was allowed without a formal hearing.

Seemingly by August 1945 this practice had more or less ceased. The article continues:

This means that the only way in which Tribunal conditions can be changed is by the case being referred back to the Tribunal.

She wondered if this explains Dennis’ tribunal – he had to go through a formal hearing in order to be released from the conditions of his inclusion on the conscientious objector register? She did add the caveat that she wasn’t an expert on all this but what she says seems highly likely if he had to officially change his conditions of registration, many months after his serious injury.

Dennis Woodcock was just one of so many that were involved in a world war, and he was lucky to survive alive. He went on to live a quiet and happy life. He could be described as just another ordinary man, but, as has been said by others, the final success of the overall war effort was achieved by ordinary men doing extraordinary things.